My Velcro Strap sail attachment—an accidental invention.

I first dreamed up this use of Velcro straps back in 2008 when I had inherited a rowing dinghy from my father in law and wanted to add a sailing rig to it. So I fitted a centerboard and added a rudder and created a mast step with a hole in the forward thwart to serve to hold a carbon fiber mast in place. The boat would be cat-rigged with only a mainsail—there was no jib.

My primary motivation for using Velcro straps was that it would make it quick and easy to get the sail rigged and go sailing. And this it most certainly did—it takes a fraction of the time to wrap the straps around the mast and seal them together, as opposed to fitting little stainless steel slides onto a track.

It takes less than a minute to attach the sail using the five Velcro straps.

Showing the five straps that attach the mainsail to the mast.

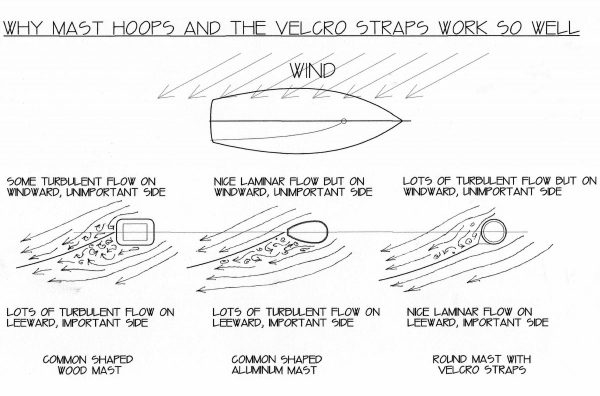

What I didn’t anticipate was that using straps instead of a track and slides or bolt rope actually made the boat perform a lot better than I expected. This became one of those serendipitous discoveries that are impossible to foresee. You can read more about why this happens in the March/April 2021 issue of WoodenBoat magazine, where they review a new 15-foot sailboat of my design that uses the straps. Basically what happens is that with the straps (or mast hoops too), the luff of the mainsail gets pushed to leeward every time the boat tacks. With a track or bolt rope groove on the aft face of the mast the luff tape is constrained to be always on centerline, creating an area of significant turbulence abaft the mast on the leeward side.

The following illustration should make this more clear:

What is important to recognize is that the leeward side of any sail generates much more of the drive than does the windward side. The “suck” propels the boat far more than the “push.” So if turbulence is inevitable abaft a mast of finite bulk, it is far better to make sure there is less turbulence on the leeward¬ more important¬ side, even though this of necessity increases the amount of turbulence on the windward side.

This is particularly important when you consider how all sails work, especially in going to windward. Picture the shape of a sail when viewed from above. The forward part of the sail is angled relative to the centerline of the yacht, while the aft part is usually almost parallel to the centerline. This means that the forward-acting force derived by the sail occurs at its forward end, while the aft part of the sail does nothing but generate sideways force, doing nothing to pull the boat forward. This being the case, there are two consequences.

First, a jib is far more important in propelling a boat than a mainsail, because its leading edge is in entirely clean, unobstructed flow. A mainsail has a spoiler (the mast) in exactly the part of the sail that is most important in propelling the boat forward- the luff.

But if you can do something—like fitting the Velcro straps—that makes the forwardmost part of a mainsail more efficient, then the sail’s contribution to propelling the boat is increased.

The importance of making the mainsail more efficient is illustrated by my longtime experience with a marconi rigged Herreshoff 12 1/2 and my modern versions, all fitted with the Velcro straps. A Herreshoff 12 ½ sails quite well with main and jib, but it is almost impossible to sail with the mainsail only. My Velcro strapped versions sail extremely well with the mainsail only, because, I believe, of the fact that the forward part of the mainsail is making a more significant contribution to the driving force.

When it comes to the details, there is mostly good news. I have never had any problem with the straps coming undone no matter how strong the wind. (A hurricane will rip the sail away no matter how it is attached). I don’t believe this will become a problem, as sails get old and sun-rotten and need replacement apparently before the Velcro begins to lose its grip.

The one potential problem is that if the straps are allowed to become too floppy or flaccid, they can “droop” and in so doing jam on the mast in hoisting or lowering—the harder you pull, the harder it jams! This definitely needs to be prevented in the construction of the straps. Basically they have to be stiffened enough that they “stick out” from the luff of the sail at a 90-degree angle, and the bias strength of the sailcloth and other materials of which they are made must prevent any tendency to droop. So one must either make the straps of overly thick sailcloth that has a high amount of bias strength, or laminate other materials such as sheet plastic or Mylar into the strap, making sure that some of it extends aft into the luff of the sail itself.

THE COMPROMISES:

As is true in everything, there are some compromises. They stem from the fact that the straps encircle the mast, so there can be no fittings in their path to obstruct their passage.

One such obstruction is the lowest stay or shroud that attaches to the mast—the uppermost strap must be located below such a stay’s attachment point. Since on my smallest designs this is roughly four feet, I found that if I didn’t have enough halyard tension, a large scallop would develop from the uppermost strap to the headboard of the mainsail. This I solved with a little help from my yacht designer brother. He came up with the perfect fix: a vertical batten alongside the luff tape in this area. Since a batten was chosen that is almost infinitely stiff fore and aft, it eliminates the scallop. The photo below should illustrate this.

This shows the vertical batten at the top of the mainsail.

Also, if one fits a spinnaker pole ring on the front of the mast, it must be located only a little way above the boom gooseneck, lest the “stack height” of the furled mainsail become too high—the lowest strap will be unable to pass by such a fitting. This then requires that on boats that fly spinnakers, the spinnaker pole is a bit lower than most of us are used to, but being a bit lower it permits a larger spinnaker to be flown.

I’ll show this photo again… the stack of straps is held up in the air by the spinnaker ring.

I have worked with a particular sailmaker right from the start, and I strongly recommend that you purchase the straps, at least, from them and preferably the entire sail that you anticipate fitting. They have so far made six mainsails to my designs with this feature, fitted to sails on yachts from 11’ to 18’ in overall length. It remains a subject of experiment, and ultimately at some point failure, to determine the upper limit of sail size using this feature.

If this article has piqued your interest, please contact the following sailmaker, who has my highest recommendation:

Steve Thurston

Thurston Quantum Sailmakers

112 Tupelo St.

Bristol, RI 02809

sthurston@quantumsails.comI wish you the best of luck with your new sail.

Chuck Paine